The pope’s autobiography styles him as “of the people,” but his past in Argentina is more complicated.

MARCH 13, 2025

I was at school in Buenos Aires when Francis became pope. I remember seeing the news on the televisions in the cafeteria: “HAY PAPA ARGENTINO” (“We have an Argentine Pope”), newscaster Julio Bazán exclaimed with genuine shock in his eyes. “Habemus Papam,” the Latin phrase announcing the election of a new pope, became a meme overnight.

Jorge Mario Bergoglio was the first ever Latin American pope, and the first since the Syrian Gregory III (whose papacy lasted from 731 to 741) to be of non-European extraction. In Argentina, whose population is roughly 63 percent Catholic, people celebrated Bergoglio’s ascendancy to the papacy with jubilation in the streets; thousands headed to the country’s cathedrals waving Argentine flags. Suddenly every bus in the city of Buenos Aires seemed to sport, on its dashboard, a holy card of the pope. Our pope.

Twelve years later, Bergoglio — who styled himself Francis after Saint Francis of Assisi, a “man of the poor” — has become a symbol of a church transformed. With his commitment to humility and socially engaged priestly leadership, he has established a new role of moral authority for the papacy. Improbably rescuing the church’s image following the pedophilia scandal that his predecessor, Benedict XVI, failed to address, he has since become a powerful advocate for migrants’ rights and the inclusion of queer people in the church, and against war and brutality in Sudan, Gaza, Yemen, Ukraine, and beyond.

He also remains a major figure in the Argentine imagination, beloved and admired by many. A 2008 photograph of Francis — then cardinal and the archbishop of Buenos Aires — looking into the camera clad in Jesuit black while riding the Buenos Aires subway periodically goes viral on Argentine Twitter as proof of his “aura.” In his autobiography, Hope, published in January and co-written with the Italian author Carlo Musso, Francis insists that his Argentine and Latin American origins and intellectual background — a Catholic tradition that is politically and socially committed, at times even radical — are central to his theology.

Though his papacy is almost universally admired, Bergoglio’s reputation in Argentina is more nuanced. His political allegiances and pronouncements have often angered opponents on either side of Argentina’s politics. His efforts to heal the Catholic Church’s scarred reputation in the country have, on occasion, backfired, damaging the image of the church as well as his own.

✺

Bergoglio’s story, as he tells it in Hope, begins with his family’s migration from the impoverished, rural Piedmont region of Italy. A prologue tells the story of the SS Principessa Mafalda, a famous ship that sank off the coast of Brazil in October 1927, killing hundreds; Bergoglio’s grandparents and their son, his father, had tickets for that journey, which they narrowly missed after failing to sell their belongings in time. They emigrated a year and a half later, in February 1929. His mother was born in Argentina to an Italian family who had emigrated decades prior.

In Hope, he expounds on his commitment to city life and being among people: “The streets tell me so much, I learn a lot from them. And I enjoy the city, above and below, the streets, piazzas, taverns, and a pizza eaten on an outside table, which has quite a different flavor from the one that’s delivered to you: I’m a citizen at heart.”

Bergoglio came of age in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Flores, a “complex, multiethnic, and multicultural microcosm.” He knew Muslims, Armenians, Italians, Spaniards, Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews: “Difference was the norm, and we respected each other,” he insists with a hint of nostalgic idealization. His father’s family attained some degree of financial comfort in Argentina, but had lost most of it by the time Bergoglio and his siblings were born. They were, he suggests, “respectably poor.” Bergoglio’s grandfather even had a minor political career in the Radical Civic Union, Argentina’s first “modern,” American-style political party. Elpidio González, who was vice-president of Argentina in the 1920s before rejecting the privileges that came with his former office and embracing poverty, was a regular presence in the house. Bergoglio knew him only as “Don Elpidio.” “In some ways, we were an elitist family though incongruously so since we were certainly not rich,” he writes.

His own youth and his family’s arduous journey to arrive in the New World explains, in part, Francis’ later commitment to a humble, justice-focused papacy. In Hope, he expounds on his commitment to city life and being among people: “The streets tell me so much, I learn a lot from them. And I enjoy the city, above and below, the streets, piazzas, taverns, and a pizza eaten on an outside table, which has quite a different flavor from the one that’s delivered to you: I’m a citizen at heart.” As a freshly ordained priest, in 1970, Bergoglio gave last rites to Azucena Maizani, a tango star not known for her Catholic virtue; as an archbishop, he gave a private mass for a group of prostitutes he knew from Flores.

He also writes movingly of Esther Ballestrino de Careaga, a Paraguayan biomedical pharmaceutical researcher who had taken refuge in Buenos Aires after being persecuted by Paraguay’s 1940s dictatorship for her Marxist and feminist activism. Ballestrino was Bergoglio’s boss when he was a chemical technician in training (his uncles had counseled him to pursue a technical degree in high school). They kept in touch after he graduated and went into seminary. Though he disagreed with her Marxist beliefs, she taught him not only “the meticulous care” required in scientific work, but “to think, by which I mean, to think about politics.” After the military regime in Argentina disappeared her family members, Ballestrino, an atheist, asked him to hide her left-wing books (potential proof of her “subversive” activities), which he stored at the Jesuit school where he was teaching. Later that year, Ballestrino began to attend the meetings and demonstrations of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, a group of women who protested in search of their disappeared families. She was kidnapped in 1977 and never seen again.

As church officials’ activities during the dictatorship started to become public, Bergoglio came under suspicion from the public and the media, despite his record of quiet opposition to the regime.

In Hope, Francis is critical of the cruelty and terror of the military dictatorship, which took power with a coup in 1976 and waged a campaign of clandestine terror and violence against suspected left-wing opponents until the return of democracy in 1983. He denounces the killing of political opponents and the persecution of left-wing priests; he recalls smuggling an endangered clergyman across the border to Brazil and the San Patricio Church massacre, in which the regime’s clandestine forces killed five clerics associated with the Pallotine Catholic order. The dictatorship “stamped out any form of dissent in cultural, political, social, trade union, or university circles,” he writes. An ongoing trial for crimes against humanity has also revealed that Francis worked to ensure the liberation of a former student who’d been kidnapped by the regime’s “task groups.”

Hope skirts the uncomfortable fact that the Catholic Church’s leadership was enthusiastically in favor of the military dictatorship.

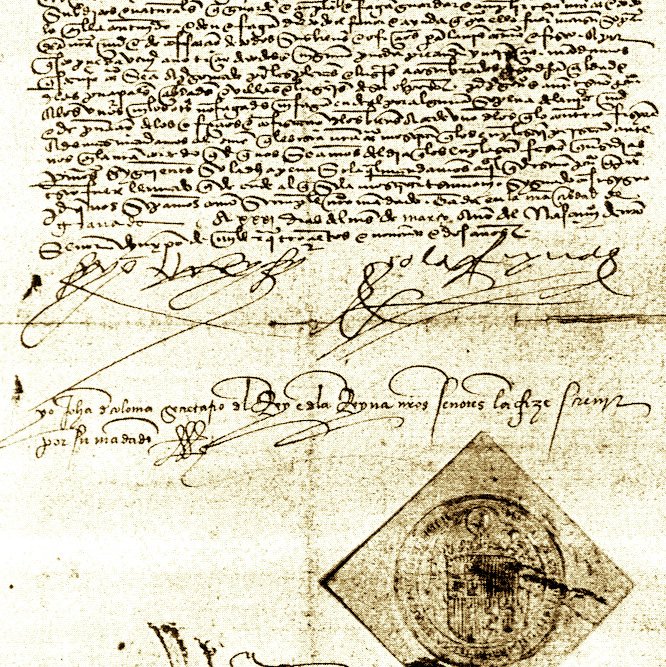

As Catholic journalist and historian Emilio Mignone has documented, would-be dictators General Jorge Rafael Videla and Admiral Emilio Massera met with church leaders the night before their March 1976 coup and on the day itself, receiving guarantees of support. The then archbishop of Buenos Aires, Adolfo Tortolo, was close friends with Videla, the regime’s first and most brutal leader. Before and after the coup, Tortolo was the country’s military chaplain in charge of the armed forces’ religious corps. Though the military regime was broadly popular initially, it soon lost favor among Argentines. Support from the church leadership, however, remained unwavering until the end despite reports of widespread torture and extrajudicial murders immediately following the coup.

Bergoglio's role at the time meant that he was at a remove from the church’s decision to support the military coup. He held a position of authority outside of the ecclesiastical hierarchy: From 1973 to 1979, he was the leader of Argentina’s Company of Jesus (i.e. the Jesuit order), and thereafter the rector of the Colegio Máximo, a Jesuit institution of higher learning in the suburbs of Buenos Aires. Two Jesuit priests who worked in a Buenos Aires slum, Orlando Yorio and Ferenc Jálics, were kidnapped by the regime in May 1976 and held captive for months before being released and fleeing the country. The Archbishop of Buenos Aires, a cardinal, had removed them from the Catholic Church’s roster of priests a week earlier. The dictatorship suspected priests who preached in shanty towns of involvement in armed struggle and pressured church leadership to cut ties or remove them from the slums.

Bergoglio said, in 1999, that he met with Videla and Massera multiple times to request the priests’ release and, upon their liberation, helped them leave Argentina. But as church officials’ activities during the dictatorship started to become public, Bergoglio came under suspicion from the public and the media, despite his record of quiet opposition to the regime.

Allegations that Bergoglio had authorized the kidnappings, which he denied, were published first by Mignone in a book in 1986. They were repeated between 2005 and 2010 in Página 12, a publication that openly supported the new center-left government led by Néstor Kirchner. The allegations came at a time of conflict between Bergoglio, who had become archbishop of Buenos Aires in 1998, and Kirchner, the new president. Kirchner had, a year earlier, backed sanctions for clergymen who publicly opposed the government’s human rights policies, including his decision to annul laws pardoning dictatorship-era atrocities. Bergoglio opposed the levying of such sanctions against priests who spoke out against these policies. In 2010, Kirchner’s successor and wife, Cristina Fernández, passed a law legalizing gay marriage, to which Bergoglio was strongly opposed, going so far as to ask an order of nuns to wage “God’s war” against the project. (Soon after Bergoglio became pope, in 2013, Página 12 took down the pieces alleging his complicity in the kidnappings of the Jesuit priests, though it continued to defend its reporting.)

In 2017, authorized by Francis, Argentina’s diocese for the first time opened its archives from the period between 1966 and 1983 to select researchers, to conduct an investigation. This investigation, in which Bergoglio is not mentioned, describes the activities of various church leaders and demonstrates the proximity between the church and the military regime. The archives on which the investigation relied, however, have not yet been made public. Hope does not delve into any of this history.

✺

The role of the pope is to focus on global Catholic affairs. But Argentina’s political culture does not allow for neutrality — especially for religious leaders, who hold the ear of the country’s many Catholic faithful.

After he took the Throne of Saint Peter, in 2013, Francis remained an opponent of then-president Fernández de Kirchner. He was expected to align himself, publicly or privately, with wealthy businessman Mauricio Macri’s center-right opposition party; he also had a long-standing relationship with Gabriela Michetti, a key adviser to Macri and his eventual vice-president.

Such side-taking has inevitably earned Francis detractors over the years: A Pew poll, for instance, found that support for him among Argentine Catholics had fallen from 98 percent in 2013 to 74 percent in 2024.

Yet Macri, after he was elected president in 2015, met with Francis only twice during his four-year term. On his first trip to the Holy See, Francis’ unsmiling welcome was seen as frigid and unfriendly; both encounters were markedly brief. Though reluctant to intervene too explicitly in Argentine politics, Francis criticized the social costs of Macri’s economic program, which mostly consisted of austerity measures and an unsustainable deregulation of the dollar exchange rate. In 2018, while visiting Chile and Brazil, Francis flew over Argentina in a gesture interpreted as a rebuff of Macri’s austerity policies. Meanwhile, Francis’ relationship with Fernández and other Kirchnerists grew stronger, and he frequently received her or her allies in the Vatican.

Javier Milei, Argentina’s current far-right president, called the pope an “imbecile” and “the representative of the evil one on Earth” in 2020. He has also claimed that Francis had “an affinity for the murderous communists” of Argentina in the 1970s. In early 2024, following Milei’s electoral victory, Francis invited him to the Vatican. Milei apologized for his previous statements and the encounter was friendly, with the Pope commenting jokingly that Milei had “cut [his] hair.” But Francis has since expressed displeasure at the harsh social consequences of Milei’s shock doctrine economic policies and in September, following the repression of protests across the country, he said that the government had “paid for tear gas instead of social justice.”

Such side-taking has inevitably earned Francis detractors over the years: A Pew poll, for instance, found that support for him among Argentine Catholics had fallen from 98 percent in 2013 to 74 percent in 2024.

But Francis is no longer Bergoglio, and Hope makes clear that his preoccupations are now global, as is his congregation. His harshest words are directed toward those waging war or manufacturing weapons, as well as toward those who refuse to take in the refugees and migrants that war produces. He denounces the Hamas attack of October 7, 2023, affirming that he “lost Argentinian friends in that carnage,” and is sharply critical of the subsequent Israeli “barbarity,” which has killed nearly 50,000 Palestinians. He also speaks of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and how he attempted to foster peace by contacting both governments and offering himself as mediator. (The Russian ambassador rebuffed him.) War, he writes, is “madness, [while] peace is rational, because it reflects and fulfills human nature and people’s natural aspirations.” He allows for a fuller inclusion of women into the clergy — saying the question is “open to study” — and supports the church’s duty to baptize and accept as witnesses or godparents both gay and transgender people.

Francis has repositioned the scandal-ridden church he inherited as an advocate for social welfare and peace, fulfilling the tenets of his “People’s Theology.” Most recently, he sparred with U.S. President J.D. Vance over his use of Catholic theology to justify mass deportations. In July 2024, he excommunicated the far-right Italian archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, whom he accused of schism.

At the time of writing, the pope lies in hospital in serious condition. No matter the outcome, Francis, more than Bergoglio, will be remembered as an advocate for the poor and least fortunate in a world headed toward the intolerance and nativism against which he built his church.

IMAGE: Illustration using photos of Pope Francis and Buenos Aires (via Wikimedia)

✺ Published in “Issue 26: Gospel” of The Dial

Eduard Habsburg, with the help of his royal ancestors, wants to fix your marriage, your soul, and your politics.

Is Spain’s citizenship program for Sephardic Jews the best way to right past wrongs?

FEDERICO PERELMUTER is a writer and journalist based in Buenos Aires.